Encryption has never been more important for — but it’s too often misunderstood

Andrei Mihai

We’ve never communicated online more than we do now. The world is becoming more and more interconnected, and it’s not just globalization and the ever-growing expansion of the internet — the pandemic has also played a role. Although many are gradually returning to the office, an unprecedented number of people are working from home, which means they’re communicating and sending potentially sensitive information online.

Thankfully, we have encryption.

Nowadays, end-to-end encryption is how most messages are sent around the world, but increasingly, some governments are trying to do away with encryption and ensure they have a way of breaching into messages when it would be deemed necessary. This could help discover and stop acts of terror but it could also make it easier for third parties such as internet providers and even the authorities to snoop in on people’s conversations.

Even ignoring the complex and ethically challenging issues associated with this idea, there are also major technical hurdles that would need to be overcome, and it’s not clear how this would be done.

Encryption 101

Think of it this way: Alice wants to send a letter to Bob, but she fears the mailman will read the letter and she doesn’t want that. So she buys a lockbox with two keys. If she can meet up with Bob somehow and give him one of the keys (because she can’t send it via email, otherwise the mailman can intercept the message), she has ensured a form of end-to-end encryption.

In this simplified example, the two are sharing messages over an unsafe channel, and have devised a way to ensure the privacy of their message. Of course, online encryption is much more complex, and there are several types of encryption.

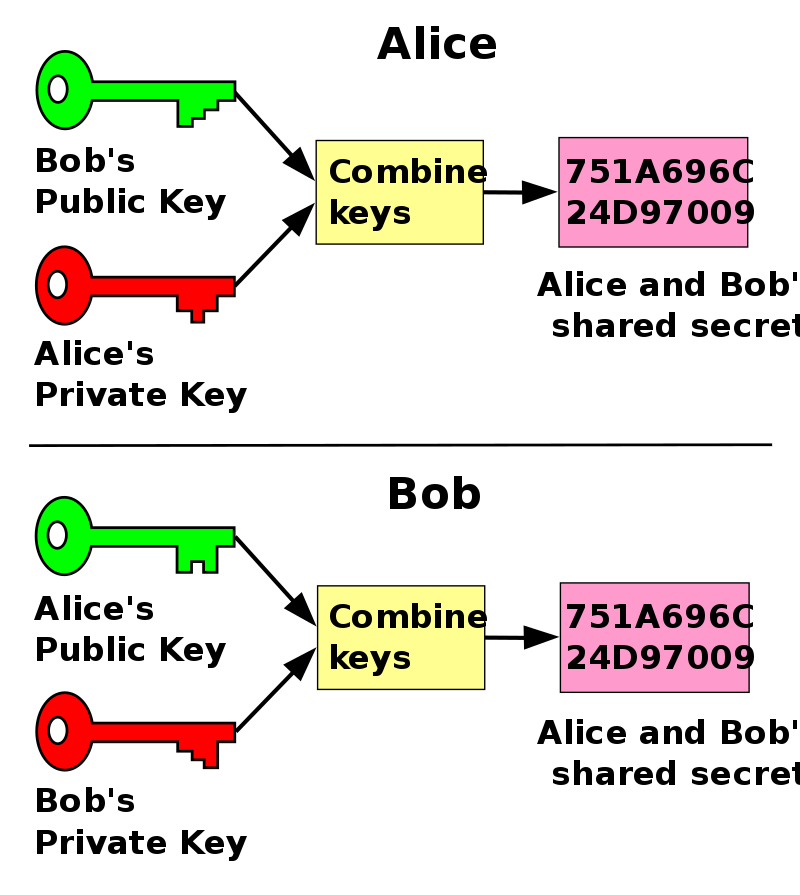

An important form of encryption was also proposed by Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman, who received the ACM Turing Award in 2015 and have attended the Heidelberg Laureate Forum. Their work is the backbone of the modern encryption we rely on today.

A struggle for encryption

Governments tend to dislike encryption because they make it harder for them to catch criminals. Users like their privacy, and tech companies like to operate as freely as possible. The tug-and-pull between authorities, companies, and the public is bound to be complex. To make it worse, at least in some instances, authorities have shown a striking disregard for user privacy — or simply a lack of understanding regarding how encryption works.

For instance, in 2017, then UK Home Secretary Amber Rudd called for end-to-end encryption to be banned, claiming “real people” don’t need it. Rudd also wanted to force companies to install a “backdoor” that would offer authorities the possibility of tuning into conversations when it would be deemed necessary. The UK government proposal said, “you don’t even have to touch the encryption” to install something like this — but that’s hardly true.

Several similar proposals (if not in form, at least in spirit) have emerged in the past few years. In the EU, officials have recently called for companies to build ways to break into their own encryption. In India, new rules for messaging services undermine people’s ability to have a private conversation, and in Brazil, the Supreme Court may soon decide whether the government can shut off encrypted messaging services. In China, there is virtually no end-to-end encryption, as the Cryptography Law offers the government full access to all encrypted content and communication companies are required to turn over all user data.

While you could try attempt to justify the ethical implications of these proposals (and that’s a big conversation in itself) the technical challenges are not trivial — and unfortunately, they are too often ignored by officials.

“Rudd’s comment reflected tremendous ignorance about how modern communication works,” noted Dr. Paulo Garcia, Systems and Computer Engineering at Carleton University, Ottawa, in a recent article. “The proposal, referred to informally as ghost protocol, is a more strategic attack on privacy, packaged in security rhetoric that hides technical, personal and societal implications.”

No middle way

When it comes to end-to-end encryption, which is currently the preferred approach of many large online companies, there’s no middle way: it’s either encrypted, and it’s not. If a conversation is truly end-to-end encrypted, the messaging company couldn’t turn over the data even if they wanted to. This is why, increasingly, there is political pressure to undermine or outright ban encryption.

Proposals like Rudd’s (which seem to be gaining more and more traction) would have companies add a new user to encrypted conversations. This “ghost” user (officials) would be able to access the conversation only in legally approved situations, but it would require messaging apps to change how keys are negotiated among participants. This would not just add more complexity to the system, but also more vulnerability.

For instance, it would make it much easier for messaging companies to gain access to users’ conversations (something which is not currently possible with true encryption). Even an employee with enough power would be able to have a peak at conversations.

Furthermore, this would create an important point of failure: should an attacker hack into the messaging app, they could access the ghost user and inject themselves into any conversation. Essentially, ghost protocols would make it so that encrypted conversations are not really encrypted anymore. So contrary to what Rudd claimed, a ghost protocol would involve a lot of changes, and these changes could further jeopardize user privacy.

If one or several countries were to mandate this type of protocol, it’s also not clear how the messaging platform would implement different types of encryption. Would there be two different versions of the platform that work in parallel? What happens when users from countries with different encryption laws want to talk to each other? It’s not clear how these problems (and many more) would be overcome.

Ultimately, the problem of encryption is a very human one, and it can largely be summed in one question: should two people, regardless of where they are in the world, be allowed to have a completely private conversation? People have private in-person conversations all the time, and few would argue against this right, yet somehow, when the conversation takes place online, the matter is much more contentious.

The post Encryption has never been more important for — but it’s too often misunderstood originally appeared on the HLFF SciLogs blog.